Flo app controversy: Jury rules Meta stole users' menstrual data.

Millions of women entrusted their menstrual data in the period cycle app, Flo. Now the court ruled Meta was eavesdropping on users' in-app communications. But why would Meta want your menstrual data, and what does it mean for your privacy?

To many women, Flo seemed like the perfect way to monitor their menstrual cycles privately with a smartphone. The app developers had promised to keep women’s private data regarding their reproductive health private. But in the background, Big Tech – as well as the Flo app itself – were watching. According to the lawsuit, the Flo app allowed Meta and Google to eavesdrop on users’ in-app communications between November 2016 and February 2019, which violates California’s Invasion of Privacy Act.

On August 4th 2025 the verdict was concluded and found that Meta had “intentionally eavesdropped on and/or recorded conversations using an electronic device,” without users of the Flo app knowing. For now, the financial damages have not been decided, and Meta has objected to the verdict.

This conclusion by the court finalizes the lawsuit filed in 2021 against Google, Meta, Flo, and Flurry, the app analytics company, where Flo users blamed the companies of collecting their private data from the Flo app without their consent for targeted advertising. This verdict made by the court in California against Meta highlights how greedy the tech giant is for your data. And the reason? To sell you more stuff through targeted advertising.

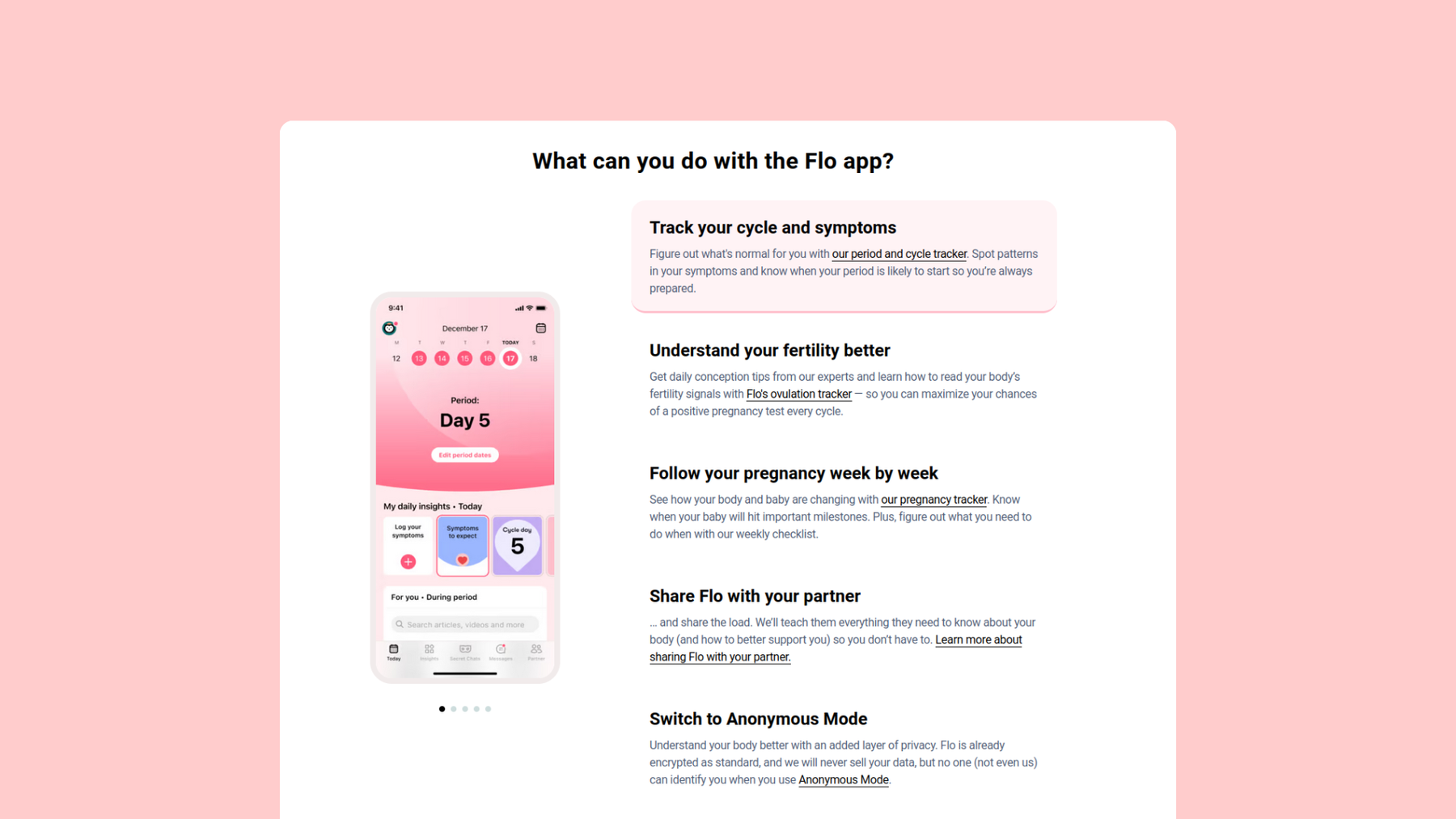

The Flo app has many features that are useful for females to track their menstruation and fertility, but in order to use these features, a lot of intimate data needs to be shared with the app. Screenshot: Flo.Health

How the Flo app controversy started

In 2021, Erica Frasco filed a class action lawsuit against Flo Health after The Wall Street Journal reported on its privacy issues in 2019. Like millions of other women who believed they were using the menstrual app privately, she answered extremely intimate questions. The questions varied, from preferred birth control methods, to the level of satisfaction with their sex life, to whether they were trying to get pregnant.

The problem according to the complaint is that the Flo app had promised its users that it wouldn’t share this private data with third parties, except if it was necessary for the provision of its services – but even in this case, it said it would not include “information regarding your marked cycles, pregnancy, symptoms, notes and other information entered by [users]”. But as it turns out this was not true. Instead, it was another prime example of privacy washing – a marketing tactic that has become as popular in the tech industry as green washing in the automotive industry.

Between 2016 and 2019, users’ confidential and intimate data was shared with companies like Facebook, Google, and Flurry. This included when its users opened the app and their interactions in the app. According to the complaint, Flo Health also didn’t regulate how the third parties could use its users’ intimate data.

Users on Reddit shared their opinion over the news that Meta had illegally collected the intimate data of women using the Flo app. Screenshots: Reddit

Why would Meta want your Flo app menstrual data?

We’ve done a lot of reporting on Meta’s companies like Facebook and Instagram, and one thing is clear: All Meta apps track us and watch our every move online so that the tech giant can collect our data, target us with ads, and make a huge profit. This is why Meta services are free to use. Only if you’re in the EU, you can pay to go ad-free. If you want to be really scared, check how much Facebook knows about you.

But even though we know Meta profits from user data, it still feels like such a far push that Meta would illegally collect women’s intimate data from the Flo app for targeted advertising. And for the millions of people who entrusted the Flo period app with their reproductive data, it’s worrying that this data was collected by Meta and the other companies involved.

Loss of trust

As we spend more time online, we are encouraged to install apps, buy things, and share our information. But something we need to be aware of is that even though these apps and services can be helpful, they often come with risks such as how they process and share our data. Of course, these risks are disclosed in terms of use, which many don’t read, but even if they do, it can be pointless. In the case with the Flo app, the developers and tech giants were outright lying to the users and abusing their data without asking for consent.

What do we learn? With the current digital landscape, and our digital identities containing more personal data than ever, the case of the Flo app controversy should be a reminder to be cautious online and think twice, especially when sharing intimate or confidential information. Also remember that sometimes it’s better to have fewer apps; because most free apps make money by tracking you.