Using Google's location tracking can put innocents in jail.

Geofencing requests - despite violating privacy rights - are being issued more frequently in the US every year.

How a bike ride made Zachary a suspect

The most recent example is Zachary McCoy, who was the prime suspect in a case of burglary due to a bike ride. Data from his fitness app showed that he had passed a burglarized home in his neighborhood three times during the timeframe of the burglary.

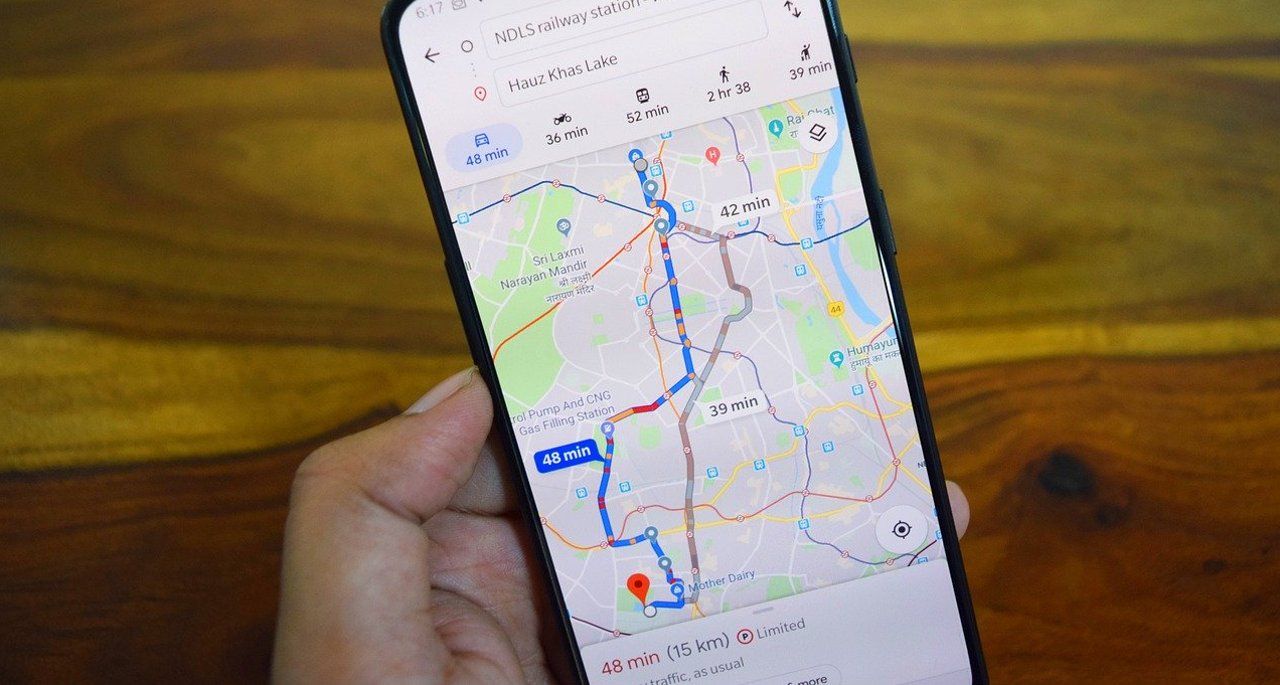

As police had no clue who might have been the burglar, they sent a geofencing warrant to Google. This is a police surveillance tool that casts a virtual net over a crime scene, scooping up Google location data — drawn from users’ GPS, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and cellular connections — from everyone in the area in a given timeframe.

The data showed that Zachary had passed the house three times on his bike, which made him the prime suspect for the police. Zachary was notified about the investigation by an email from Google. Being scared, his parents dipped into their savings to pay thousands of dollars to a lawyer to make sure their son would not go to prison for a crime that he never committed.

The case against Zachary was eventually closed, but it shows that even when being innocent, you can still be in the wrong place at the wrong time - and in some cases you can even get jailed for being at the wrong place as another example from Arizona shows.

Being jailed because of Google data

In 2018 an innocent man was jailed for six days in Avondale, Arizona, because his Google data showed that he had been at the scene of a shooting where one person was murdered. To make things worse his car had been spotted on surveillance cameras in the area as well.

Later it turned out that the suspect’s stepfather had used his car and had a device with him, on which the suspect’s Google credentials where logged in. By now, the innocent suspect has filed a lawsuit against the authorities because while prosecutors never pursued charges against him, he lost his job, his car and his reputation due to the investigation, during which the police also released his full name in a press release. He was also unable to find a new job because a quick Google search showed that he had been investigated for murder so he did not pass background checks.

Tracking and geofencing

The two cases show one thing very clearly: Al data that is accessible, is being used - whether you like it or not, even whether Google likes it or not. Google has to comply with warrants as any other company in the world.

The problem is that today much more data about us exists than we can even imagine. The authorities are quickly learning how to get hold of this data, and despite the fact that general geofencing warrants are violating privacy rights, these are widely issued by judges in the US.

Fishing expeditions by the police

Google said in a court filing last year that the requests from state and federal law enforcement authorities were increasing rapidly: by more than 1,500 percent from 2017 to 2018, and by 500 percent from 2018 to 2019.

”This fishing expedition infringes on the privacy rights of so many possible people who had the misfortune of being in an area where a crime is alleged to be committed,” said Jerome Greco, staff attorney at the Legal Aid Society to Forbes. “We should not allow for such broad access to the data of so many on the mere speculation that a suspect may have used a cellphone near the location of the crime.”

Police officers described the data they obtained from Google as “incredible”. People would not realize to what extent they are being tracked - not by the government, but by private companies such as Google.

Mass surveillance vs. targeted investigation

Free and democratic republics value privacy and data protection rights and limit investigators’ power to only obtaining data about specific suspects. This method has been estalished decades ago to prevent turning an innocent citizen into a crime suspect without probable cause.

The two examples described earlier show how quickly the data accumulated by Google can turn innocent people into prime suspects of crimes.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation calls these reverse location warrants problematic, to say the least, for several reasons:

“Unlike other methods of investigation used by the police, the police don’t start with an actual suspect or even a target device—they work backward from a location and time to identify a suspect. This makes it a fishing expedition—the very kind of search that the Fourth Amendment was intended to prevent. Searches like these—where the only information the police have is that a crime has occured—are much more likely to implicate innocent people who just happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Every device owner in the area during the time at issue becomes a suspect—for no other reason than that they own a device that shares location information with Google.”

Plus, “there’s a high probability the true perpetrator isn’t even included in the data disclosed by Google. For these kinds of warrants, officers are just operating off a hunch that the unknown suspect had a cellphone that generated location data collected by Google. This shouldn’t be enough to support probable cause, because it’s just as likely that the suspect wasn’t carrying an Android phone or using Google apps at the time.”

Warrants don’t help with privacy infringements

This technique demonstrates that demanding warrants alone is not satisfactory to protect our privacy anylonger. When warrants are being issued for fishing investigations based on a ‘hunch’ that the suspect might have used a Google device, basic privacy protection rights are being violated.

Data minimalization

As governments around the world push for more surveillance, it’s best for us to leave Google and use only privacy-respecting services and for companies to build their services based on privacy by design. Data should only be stored inaccessibly to the provider. This is the only way that general fishing warrants will become pointless.

With the coronavirus pandemic boosting tracking technologies around the world, we must take even more care that our data is stored or decrypted locally on the users’ devices instead of consolidating all data on a single server, easily accessible not only by the authorities, but also by malicious (state) actors and other third parties who will go to great lengths to tap into this powerful data collection.

Privacy is a Human Right. We must never forget that.